Dually Diagnosed Patients Need Effective Treatment

by Robin LaSota and Martha Yeide

As Fellows in the Minority Fellowship Program, you know the challenges individuals often face finding adequate care to address behavioral health issues. Adequate access to and disparities in care can become even more problematic when individuals experience mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs)—that is, when they are diagnosed with co-occurring disorders (CODs).

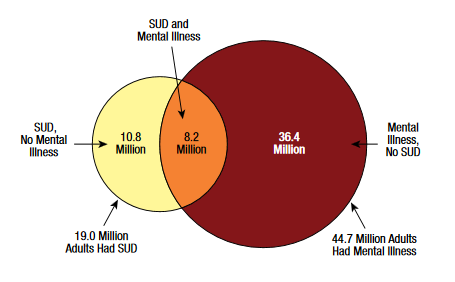

The prevalence of CODs is substantial. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, about 8.2 million Americans, or 3.4 percent of U.S. adults ages 18 and older, reported CODs in the past year.1 Of the 19.0 million adults with a past-year SUD, 8.2 million (43.3 percent) also had a mental illness in the past year. This contrasts sharply with the 36.4 million (16.1 percent) of adults who reported a mental illness but no substance use disorder in the past year. Similarly, of the 44.7 million adults with any mental illness in the past year, 8.2 million (18.5 percent) also met the criteria for an SUD in the past year. This contrasts sharply with the 10.8 million adults (5.4 percent of the adult U.S. population) who met the criteria for an SUD but did not have any mental illness.2

Co-Occurrence Notably Higher in Certain Populations

In some populations, co-occurrence is even higher. In one study of veterans, for instance, Seal and colleagues (2011) found that 63 percent of veterans who met criteria for alcohol or drug use disorders also met criteria for PTSD, and that 76 percent with both alcohol use disorder and drug use disorders also had PTSD.3 In addition, 80 percent to 95 percent of veterans with an alcohol or drug use disorder diagnosis had at least one other mental health diagnosis and were 3–4 times as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD and depression.4

Why is the prevalence of CODs so high? Several analytical frameworks have been developed that explain this high prevalence. One of these, the so-called genetic factors model, finds that genetics plays up to 60 percent of the cause of an individual’s vulnerability to addiction.5 Both Kurti and colleagues (2016) and Jos, Cooper–Sadlo, and Stillwell (2013) have identified multiple environmental risks (e.g., poverty, educational/vocational difficulties, isolation, and living in neighborhoods with a high concentration of drugs) that can all contribute to the development of CODs.6 Also, for those with existing MHDs, developmental experiences, along with experiences of trauma, can exacerbate SUDs.7 Finally, stress is another major risk factor that serves as a neurobiological link between SUDs and MHDs.8

Integrated Treatment a Promising Model

As future and current behavioral health practitioners, how should you handle such patients? The prospects for individuals with CODs can be quite negative. Negative outcomes associated with such individuals include an increased probability of high rates of relapse;9 hospitalization10 and poor health;11 incarceration;12 unemployment;13 and homelessness.14

The Seal and colleagues (2011) study mentioned above illustrates some of the challenges: Practitioners may need to help individuals with one or more substance misuse problems (alcohol and prescription drug abuse, for example) and one or more mental health issues (e.g., PTSD and depression). The combination of problems likely differs for each individual patient, and dual diagnosis patients often experience more persistent and severe symptoms that are resistant to treatment.15 As a result, they require more complex treatment than the traditionally separate mental health and substance use systems provide.16

In traditional systems of care, individuals have largely been treated sequentially (for example, first for one problem and then the next) or in parallel (that is, where one system concentrates on the mental health and a different system or set of services on the substance use).17 These models continue to thrive, in part because mental health and substance use treatment systems remain separate and often are forced to compete for the same limited resources.18

Research indicates that a more successful model is integrated treatment, which views both disorders as primary and treats them simultaneously through coordination of care across agencies, bundled interventions, or through multiple providers working together on one team and/or in one setting. Research has indicated that integrated treatment programs are more effective than nonintegrated ones.19 Additionally, the effectiveness of medications varies by dual diagnosis subgroups and medication type, and is more effective when combined with psycho-behavioral interventions.20 Integrated treatment models have been found to mitigate patients’ risks, reduce treatment costs, and promote individuals’ recovery, independent living, and employment.21 Integrated treatments have also produced positive outcomes in substance use, psychiatric functioning, hospitalization, housing stability, arrests, and quality of life.22

Three Treatments Worth Consideration

Various integrated treatment models are available. For instance, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), which integrates the treatment of severe MHDs and SUDs, is a client-centered program that provides psychiatric treatment, rehabilitation, and support services.23 The model emphasizes an individualized approach to the relationship between the client and treatment team, which includes social workers, counselors, nurses, and psychiatrists.24 Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) uses state-of-the-art assessments and combines pharmacological, psychological, educational, and social interventions aimed at clients, their families, and friends.25 An IDDT team consists of a team leader, a case manager (or case managers), specialists, a psychiatrist, a nurse, and members of the employment, housing, and criminal justice communities.26 Residential Integrated Treatment involves fulltime programming in which clinicians address patients’ mental illness and substance use disorders concurrently through two or more curricula.27

The good news for you as you move into the workforce, then, is that effective modules for treatment exist for a challenging group of patients. The barrier you then may face is finding ways to promote integrated models of treatment in systems that may privilege separate but less effective treatment for your patients.

References

The prevalence of CODs is substantial. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, about 8.2 million Americans, or 3.4 percent of U.S. adults ages 18 and older, reported CODs in the past year.1 Of the 19.0 million adults with a past-year SUD, 8.2 million (43.3 percent) also had a mental illness in the past year. This contrasts sharply with the 36.4 million (16.1 percent) of adults who reported a mental illness but no substance use disorder in the past year. Similarly, of the 44.7 million adults with any mental illness in the past year, 8.2 million (18.5 percent) also met the criteria for an SUD in the past year. This contrasts sharply with the 10.8 million adults (5.4 percent of the adult U.S. population) who met the criteria for an SUD but did not have any mental illness.2

|

In some populations, co-occurrence is even higher. In one study of veterans, for instance, Seal and colleagues (2011) found that 63 percent of veterans who met criteria for alcohol or drug use disorders also met criteria for PTSD, and that 76 percent with both alcohol use disorder and drug use disorders also had PTSD.3 In addition, 80 percent to 95 percent of veterans with an alcohol or drug use disorder diagnosis had at least one other mental health diagnosis and were 3–4 times as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD and depression.4

Why is the prevalence of CODs so high? Several analytical frameworks have been developed that explain this high prevalence. One of these, the so-called genetic factors model, finds that genetics plays up to 60 percent of the cause of an individual’s vulnerability to addiction.5 Both Kurti and colleagues (2016) and Jos, Cooper–Sadlo, and Stillwell (2013) have identified multiple environmental risks (e.g., poverty, educational/vocational difficulties, isolation, and living in neighborhoods with a high concentration of drugs) that can all contribute to the development of CODs.6 Also, for those with existing MHDs, developmental experiences, along with experiences of trauma, can exacerbate SUDs.7 Finally, stress is another major risk factor that serves as a neurobiological link between SUDs and MHDs.8

Integrated Treatment a Promising Model

As future and current behavioral health practitioners, how should you handle such patients? The prospects for individuals with CODs can be quite negative. Negative outcomes associated with such individuals include an increased probability of high rates of relapse;9 hospitalization10 and poor health;11 incarceration;12 unemployment;13 and homelessness.14

The Seal and colleagues (2011) study mentioned above illustrates some of the challenges: Practitioners may need to help individuals with one or more substance misuse problems (alcohol and prescription drug abuse, for example) and one or more mental health issues (e.g., PTSD and depression). The combination of problems likely differs for each individual patient, and dual diagnosis patients often experience more persistent and severe symptoms that are resistant to treatment.15 As a result, they require more complex treatment than the traditionally separate mental health and substance use systems provide.16

In traditional systems of care, individuals have largely been treated sequentially (for example, first for one problem and then the next) or in parallel (that is, where one system concentrates on the mental health and a different system or set of services on the substance use).17 These models continue to thrive, in part because mental health and substance use treatment systems remain separate and often are forced to compete for the same limited resources.18

Research indicates that a more successful model is integrated treatment, which views both disorders as primary and treats them simultaneously through coordination of care across agencies, bundled interventions, or through multiple providers working together on one team and/or in one setting. Research has indicated that integrated treatment programs are more effective than nonintegrated ones.19 Additionally, the effectiveness of medications varies by dual diagnosis subgroups and medication type, and is more effective when combined with psycho-behavioral interventions.20 Integrated treatment models have been found to mitigate patients’ risks, reduce treatment costs, and promote individuals’ recovery, independent living, and employment.21 Integrated treatments have also produced positive outcomes in substance use, psychiatric functioning, hospitalization, housing stability, arrests, and quality of life.22

Three Treatments Worth Consideration

Various integrated treatment models are available. For instance, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), which integrates the treatment of severe MHDs and SUDs, is a client-centered program that provides psychiatric treatment, rehabilitation, and support services.23 The model emphasizes an individualized approach to the relationship between the client and treatment team, which includes social workers, counselors, nurses, and psychiatrists.24 Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) uses state-of-the-art assessments and combines pharmacological, psychological, educational, and social interventions aimed at clients, their families, and friends.25 An IDDT team consists of a team leader, a case manager (or case managers), specialists, a psychiatrist, a nurse, and members of the employment, housing, and criminal justice communities.26 Residential Integrated Treatment involves fulltime programming in which clinicians address patients’ mental illness and substance use disorders concurrently through two or more curricula.27

The good news for you as you move into the workforce, then, is that effective modules for treatment exist for a challenging group of patients. The barrier you then may face is finding ways to promote integrated models of treatment in systems that may privilege separate but less effective treatment for your patients.

References

1Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

2Ibid.

3Seal, K. H., Cohen, G., Waldrop, A., Cohen, B. E., Maguen, S., & Ren, L. (2011). Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116(1), 93–101.

4Ibid.

5Mueser, K. T., Drake, R. E., & Wallace, M. A. (1998). Dual diagnosis: A review of etiological theories. Addictive Behaviors, 23(6), 717–734. and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2010). Comorbidity: Addiction and other mental illnesses. Washington, D.C.: National Institutes of Health.

6Kurti, A. N., Keith, D. R., Noble, A., Priest, J. S., Sprague, B. & Higgins, S. T. (2016). Characterizing the intersection of co-occurring risk factors for illicit drug abuse and dependence in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Preventive Medicine, 92, 118–125. and Jos, A., Cooper–Sadlo, S., & Stillwell, D. (2013). Advancing current treatments: Women, poverty, and co-occurring disorders. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 25(3), 165–182.

7Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406. and Swendsen, J., Conway, K. P., Degenhardt, L., Glantz, M., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., . . . Kessler, R. C. (2010). Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: Results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction, 105(6), 1117–1128.

8Mueser et al., 1998; NIDA, 2010. See note 5.

9Compton III, W. M., Cottler, L. B., Jacobs, J. L., Ben–Abdallah, A., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2003). The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(5), 890–895. and Landheim, A. S., Bakken, K., Vaglum, P. (2006). Impact of comorbid psychiatric disorder on the outcome of substance abusers: A 6-year prospective follow-up in two Norwegian counties. BMC Psychiatry, 6, 44–55.

10Daratha, K. B., Barbosa–Leiker, C., Burley, M. H., Short, R., Layton, M. E., McPherson, S., . . . & Tuttle, K. R. (2012). Co-occurring mood disorders among hospitalized patients and risk for subsequent medical hospitalization. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(5), 500–505.

11Mericle, A. A., Park, V. M. T., Holck, P., & Arria, A. M. (2012). Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of co-occurring substance use and mental disorders in the United States: Variations by race/ethnicity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 657–665.

12Somers, J. M., Moniruzzaman, A., Rezansoff, S. N., Brink, J., & Russolillo, A. (2016). The prevalence and geographic distribution of complex co-occurring disorders: A population study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(3), 267–277.

13Osher, F., & Hensley, J. (2010). The public health implications of co-occurring, addictive, and mental disorders. In B. Levin, K. Hennessy, & J. Petrila (Eds.), Mental health 165 services: A public health perspective (3rd ed.) [pp. 299–318]. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. and Connor, K., Kline, A., Sawh, L., Rodrigues, S., Fisher, W., Kane, V., . . . Smelson, D. (2013). Unemployment and co-occurring disorders among homeless veterans. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(2), 134–138.

14McNeil, D. E., & Binder, R. L. (2005). Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatric Services, 56(6), 699–704. and Watkins, K., Hunter, S., Wenzel, S., Tu, W., Paddock, S., Griffin, A., & Ebener, P. (2004). Prevalence and characteristics of clients with co-occurring disorders in outpatient substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30(4), 749–764.

15Klott, J. (2013). Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders: Treating people, not behaviors. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. and Horsfall, J., Cleary, M., Hunt, G. E., & Walter, G. (2008). Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): A review of empirical evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 17(1), 24–34.

16Mangrum, L. F., Spence, R. T., & Lopez, M. (2006). Integrated versus parallel treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(1), 79–84.

17Burnam, M. A., & Watkins, K. E. (2006). Substance abuse with mental disorders: Specialized public systems and integrated care. Health Affairs, 25(3), 648–758.

18Sterling, S., Weisner, C., Hinman, A., & Parthasarathy, S. (2010). Access to treatment for adolescents with substance use and co-occurring disorders: challenges and opportunities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(7), 637–646.

19Drake, R. E., Mercer–McFadden, C., Mueser, K. T., McHugo, G. J., & Bond, G. R. (1998). Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4), 589–608. and Drake, R. E., Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L., . . . Rickards, L. (2001). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 469–76. and Drake, R. E., O’Neal, E. L., & Wallach, M. A. (2008). A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(1), 123–138. and Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., & Fox, L. (2003). Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press. and Mangrum, L. F., Spence, R. T., & Lopez, M. (2006). Integrated versus parallel treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(1), 79–84. and Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406.

20Kelly, T. M., Daley, D. C., & Douaihy, A. B. (2012). Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 11–24.

21Babowitch, J. D., & Antshel, K. M (2016). Adolescent treatment outcomes for cormorbid depression and substance misuse: A systematic review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 25–33. and Drake, R. E., McHugo, G. J., Xie, H., Fox, M., Packard, J., & Helmstetter, B. (2006). Ten-year recovery outcomes for clients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(3), 464–473. and Drake, R. E., Mueser, K. T., Brunette, M. F., & McHugo, G. J. (2004). A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 360. and Kelly, T. M., Daley, D. C., & Douaihy, A. B. (2012). Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 11–24. and Worley, M. J., Trim, R. S., Tate, S. R., Hall, J. E., & Brown, S. A. (2010). Service utilization during and after outpatient treatment for comorbid substance use disorder and depression. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(2), 124–131.

22Drake, R. E., Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L., . . . Rickards, L. (2001). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 469–476. and Harrison, J., Curtis, A., Cousins, L., & Spybrook, J. (2017). Integrated dual disorder treatment implementation in a large state sample. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), 358–366. and Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406. and Rothbard, A., Wald, H., Zubritsky, C., Jaquette, N., Chhatre, S., & Ewing, C. P. (2009). Effectiveness of a jail-based treatment program for individuals with co-occurring disorders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(4), 643–654.

23Fries, H. P., & Rosen, M. I. (2011). The efficacy of assertive community treatment to treat substance use. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 17(1), 45–50.

24Ibid.

25Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., & Fox, L. (2003). Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

26Wieder, B. L., Lutz, W. J., & Boyle, P. (2006). Adapting integrated dual disorders treatment for inpatient settings. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 2(1), 101–107.

27McKee, S. A., Harris, G. T., & Cormier, C. A. (2013). Implementing residential integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(3), 249–259.

2Ibid.

3Seal, K. H., Cohen, G., Waldrop, A., Cohen, B. E., Maguen, S., & Ren, L. (2011). Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116(1), 93–101.

4Ibid.

5Mueser, K. T., Drake, R. E., & Wallace, M. A. (1998). Dual diagnosis: A review of etiological theories. Addictive Behaviors, 23(6), 717–734. and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2010). Comorbidity: Addiction and other mental illnesses. Washington, D.C.: National Institutes of Health.

6Kurti, A. N., Keith, D. R., Noble, A., Priest, J. S., Sprague, B. & Higgins, S. T. (2016). Characterizing the intersection of co-occurring risk factors for illicit drug abuse and dependence in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Preventive Medicine, 92, 118–125. and Jos, A., Cooper–Sadlo, S., & Stillwell, D. (2013). Advancing current treatments: Women, poverty, and co-occurring disorders. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 25(3), 165–182.

7Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406. and Swendsen, J., Conway, K. P., Degenhardt, L., Glantz, M., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., . . . Kessler, R. C. (2010). Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: Results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction, 105(6), 1117–1128.

8Mueser et al., 1998; NIDA, 2010. See note 5.

9Compton III, W. M., Cottler, L. B., Jacobs, J. L., Ben–Abdallah, A., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2003). The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(5), 890–895. and Landheim, A. S., Bakken, K., Vaglum, P. (2006). Impact of comorbid psychiatric disorder on the outcome of substance abusers: A 6-year prospective follow-up in two Norwegian counties. BMC Psychiatry, 6, 44–55.

10Daratha, K. B., Barbosa–Leiker, C., Burley, M. H., Short, R., Layton, M. E., McPherson, S., . . . & Tuttle, K. R. (2012). Co-occurring mood disorders among hospitalized patients and risk for subsequent medical hospitalization. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(5), 500–505.

11Mericle, A. A., Park, V. M. T., Holck, P., & Arria, A. M. (2012). Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of co-occurring substance use and mental disorders in the United States: Variations by race/ethnicity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 657–665.

12Somers, J. M., Moniruzzaman, A., Rezansoff, S. N., Brink, J., & Russolillo, A. (2016). The prevalence and geographic distribution of complex co-occurring disorders: A population study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(3), 267–277.

13Osher, F., & Hensley, J. (2010). The public health implications of co-occurring, addictive, and mental disorders. In B. Levin, K. Hennessy, & J. Petrila (Eds.), Mental health 165 services: A public health perspective (3rd ed.) [pp. 299–318]. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. and Connor, K., Kline, A., Sawh, L., Rodrigues, S., Fisher, W., Kane, V., . . . Smelson, D. (2013). Unemployment and co-occurring disorders among homeless veterans. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(2), 134–138.

14McNeil, D. E., & Binder, R. L. (2005). Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatric Services, 56(6), 699–704. and Watkins, K., Hunter, S., Wenzel, S., Tu, W., Paddock, S., Griffin, A., & Ebener, P. (2004). Prevalence and characteristics of clients with co-occurring disorders in outpatient substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30(4), 749–764.

15Klott, J. (2013). Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders: Treating people, not behaviors. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. and Horsfall, J., Cleary, M., Hunt, G. E., & Walter, G. (2008). Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): A review of empirical evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 17(1), 24–34.

16Mangrum, L. F., Spence, R. T., & Lopez, M. (2006). Integrated versus parallel treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(1), 79–84.

17Burnam, M. A., & Watkins, K. E. (2006). Substance abuse with mental disorders: Specialized public systems and integrated care. Health Affairs, 25(3), 648–758.

18Sterling, S., Weisner, C., Hinman, A., & Parthasarathy, S. (2010). Access to treatment for adolescents with substance use and co-occurring disorders: challenges and opportunities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(7), 637–646.

19Drake, R. E., Mercer–McFadden, C., Mueser, K. T., McHugo, G. J., & Bond, G. R. (1998). Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4), 589–608. and Drake, R. E., Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L., . . . Rickards, L. (2001). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 469–76. and Drake, R. E., O’Neal, E. L., & Wallach, M. A. (2008). A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(1), 123–138. and Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., & Fox, L. (2003). Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press. and Mangrum, L. F., Spence, R. T., & Lopez, M. (2006). Integrated versus parallel treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(1), 79–84. and Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406.

20Kelly, T. M., Daley, D. C., & Douaihy, A. B. (2012). Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 11–24.

21Babowitch, J. D., & Antshel, K. M (2016). Adolescent treatment outcomes for cormorbid depression and substance misuse: A systematic review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 25–33. and Drake, R. E., McHugo, G. J., Xie, H., Fox, M., Packard, J., & Helmstetter, B. (2006). Ten-year recovery outcomes for clients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(3), 464–473. and Drake, R. E., Mueser, K. T., Brunette, M. F., & McHugo, G. J. (2004). A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 360. and Kelly, T. M., Daley, D. C., & Douaihy, A. B. (2012). Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 11–24. and Worley, M. J., Trim, R. S., Tate, S. R., Hall, J. E., & Brown, S. A. (2010). Service utilization during and after outpatient treatment for comorbid substance use disorder and depression. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(2), 124–131.

22Drake, R. E., Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L., . . . Rickards, L. (2001). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 469–476. and Harrison, J., Curtis, A., Cousins, L., & Spybrook, J. (2017). Integrated dual disorder treatment implementation in a large state sample. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), 358–366. and Kelly, T. M., & Daley, D. C. (2013). Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 388–406. and Rothbard, A., Wald, H., Zubritsky, C., Jaquette, N., Chhatre, S., & Ewing, C. P. (2009). Effectiveness of a jail-based treatment program for individuals with co-occurring disorders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(4), 643–654.

23Fries, H. P., & Rosen, M. I. (2011). The efficacy of assertive community treatment to treat substance use. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 17(1), 45–50.

24Ibid.

25Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., & Fox, L. (2003). Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

26Wieder, B. L., Lutz, W. J., & Boyle, P. (2006). Adapting integrated dual disorders treatment for inpatient settings. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 2(1), 101–107.

27McKee, S. A., Harris, G. T., & Cormier, C. A. (2013). Implementing residential integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(3), 249–259.