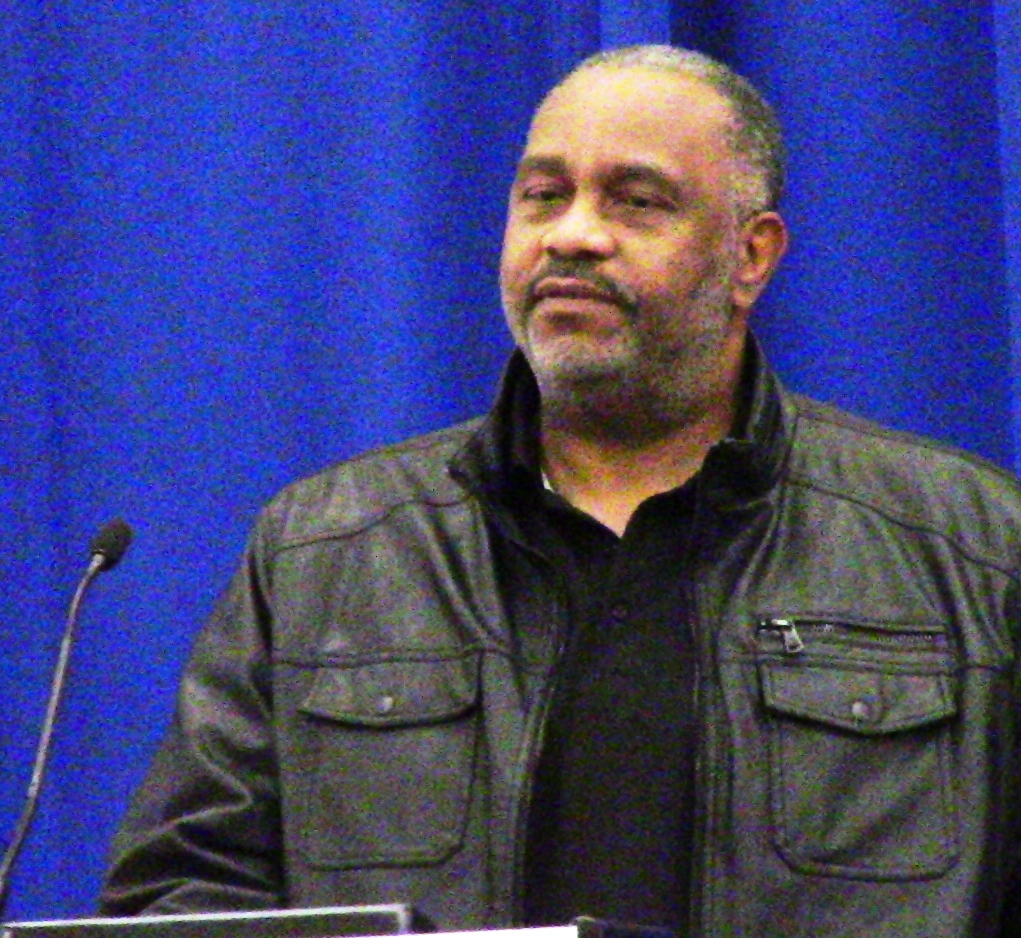

Ray Hinton |

INTERVIEW WITH A SURVIVOR OF ALABAMA'S DEATH ROW

Ray Hinton, 29 years old and African American, had just begun mowing his mother's lawn in Birmingham, Ala., one day in 1985, when he saw two white men standing on her back porch. Hinton turned off the mower and approached the men. One of them said he was looking for Anthony Ray Hinton, whom Hinton admitted he was. The men then identified themselves as a police lieutenant and sergeant and placed him in handcuffs.

At that moment, Hinton couldn't have imagined that another 29 years would pass before he was released from custody.

Hinton was charged with the murders of two Birmingham restaurant managers, in two separate robberies from earlier that year. After he told detectives that he did not own a gun but his mother did, a .38 caliber revolver was taken from his mother's home. The state of Alabama said that gun, the only evidence that would be presented at trial, was used in both murders. Hinton was convicted of those killings and sentenced to die. He spent nearly 30 years on Alabama's death row before he was released to freedom on April 3, 2015, thanks to the unrelenting efforts of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a Montgomery, Ala., nonprofit that provides legal representation to prisoners who have been denied a fair trial, but also because of his own remarkable will.

Hinton's original defense lawyer, a public defender, incorrectly believed he had only $1,000 to hire a ballistics expert to disprove Alabama's case against Hinton. The person Hinton's attorney hired was a one-eyed civil engineer with little ballistics training who admitted he had trouble operating the forensic microscope at trial.

In 1999, EJI hired ballistics experts who rapidly determined the bullets found at the two murder scenes could not have come from Hinton's mother's gun. The prosecutors refused to reopen the case.

In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Hinton's constitutional right to a fair trial had been violated.

Just 7 months free, Hinton told

his story to a packed ballroom at a Baltimore, Md., hotel Nov. 17, during the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention's conference, "Improving Public Safety and Health in Communities With High Trauma, Neglect, and Stress." Afterward, he sat down with Michael Hopps of the National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention News for a Q&A.

After those two white officers took you into custody, they wouldn't tell you for quite a while why they had placed you under arrest. Tell me again what the detective finally told you.

He turned around and said, "We arrested you for first-degree robbery, for first-degree kidnapping, and first-degree attempted murder."

What did he say when you told him you had nothing to do with anything like that?

He said: "I don't care whether you did or didn't do it. We gonna charge you for them, and you gonna be found guilty. There's five things that will convict you. Would you like to know what they are?" I said, "Yes, Sir." He said: "Number one, you black. Number two, we gonna have a white man get on the stand and say you shot them. Number three, we gonna have a white prosecutor. Number four, you gonna have a white judge. And number five, you more than likely gonna have an all-white jury."

Do you know why those two white officers were looking for you in the first place?

I was told one of the young black workers that worked at the Quincy restaurant overheard the officer say he was looking for someone with light skin, black, with a full beard. And he said, "Well, I know someone with light skin and a full beard." And they asked him, "Who?" And he gave them my name, because we played softball together. And they just come out and said, "We got a warrant for your arrest." They didn't do no investigation. The Quincy robbery that they charged me for, they never did charge me because they found out I was at work.

You were at work at the time of the robbery at which they identified a man with light skin, black, and a full beard?

That's right. They didn't charge me with what they arrested me for. They charged me for two capital murders they never had solved.

Was your public defender white?

Yes.

From the story you told the audience in the ballroom this afternoon, it sounded as though he didn't want to be there.

He didn't. He made it clear that he wasn't being paid. He said, "I didn't go to law school to do pro bono work." I asked him, "Would it make any difference if I told you I was innocent?" And he said, "All y'all say that."

You passed a polygraph test. Who administered it?

The FBI gave the polygraph test. It cost my momma $350.00. They told me that if I failed, they would use it against me and hang me. I passed it, but it was inadmissible.

What were your thoughts upon first hearing you had been condemned to die?

I was in shock. I thought, Did I hear him right? I thought, How can you say "God have mercy on your soul" when you just convicted an innocent man? Not only an innocent man, but—this is what I can't get people to understand—they knew I was innocent. They knew that gun didn't match. And they knew I had a ballistics expert who was blind. They knew he really was a civil engineer and had never done ballistics a day of his life. But that's who my lawyer hired to testify.

Could you describe death row for me?

Death row is a kind of community within a community. There are 14 cells in a row, and a cell on top of each of those. You got somebody on your left, somebody on your right, and above you, but you can't see nobody. But you make friends.

How big was your cell?

Five feet by eight feet.

Did you have visitors?

My best friend visited me every Monday.

Were you given an execution date?

No.

What was the hardest thing about being on death row?

When my family didn't come visit me, I had this voice in my head telling me to kill myself. Twenty-two men [on death row in Alabama] killed themselves while I was on death row.

How did they do it?

Bedsheets. Hanged themselves. Or cut themselves. They gave us razors. Sometimes you looked out of the cell, and you could see the blood on the ground.

Did they ever let you out of that cell?

They would let you out every other day to shower. If you showered on Monday, you'd get to shower again on Wednesday. Every once in a while—rarely—they would let you out in the yard for 30 minutes. That was the only time you saw the sun.

By what means would you have been put to death?

Electrocution.

[From 1927 to 2002, electrocution was the only means of execution in Alabama. Since 2002, Alabama has carried out the death penalty by lethal injection.]

Bryan Stevenson [founder of EJI] said your cell was 30 feet from the electric chair. Is that right?

The electric chair was 30 feet away.

What was that like?

They burned the man to death. They would have the executions at 12 a.m. on Friday. You smelled that man's skin 11, 12 hours later.

How did you manage to pass all that time in prison?

I used my imagination. I don't say this much, but I say it to young people. I mean no disrespect to women, but I would imagine I was married to Kim Kardashian. Or ... my favorite was Sandra Bullock. You have to use your imagination to give you something to hope for.

What are your thoughts on the death penalty?

A hundred and fifty-four innocent people on death row have been exonerated. How many innocent people do you think have been executed? Let's end the death penalty once and for all.

[The number of death row prisoners in the United States who have been exonerated is now 156.]

The death penalty actually affects only a tiny percentage of all our nation's citizens. Why do you think so many folks are interested in it?

It's like a car crash; everybody stops to look. When they had public hangings, people would come from all over to watch.

So, morbid curiosity?

Yes.

Was your mother there to greet you when you were released from prison?

No, my momma passed in 2002.

Where do you live today, Ray?

Birmingham.

What changes in the world have most surprised you from before you entered prison 30 years ago until now?

I have to say Walmart. If you had told me that one store would have almost anything you could think of to buy—all that good produce and anything else—I don't know what.

EJI arranged to take you and your best friend to see your beloved Yankees play the Red Sox at Yankee Stadium this year. Would you tell me one more time what a $15 hot dog tastes like?

It tastes like a $2 hot dog.