Imprisoned in Body and Mind:

Justice-Involved Youths Have High Rates of Behavioral Health Problems

by Martha Yeide and Elizabeth Spinney

Schools are thought to be great places to implement universal prevention programs, because large groups of children and youths are already gathered together there. If this is so, then by a similar (though perhaps twisted) logic, juvenile justice facilities are great places to implement substance use and mental health treatment programs. After all, there are large groups of youths with behavioral health issues gathered together there.

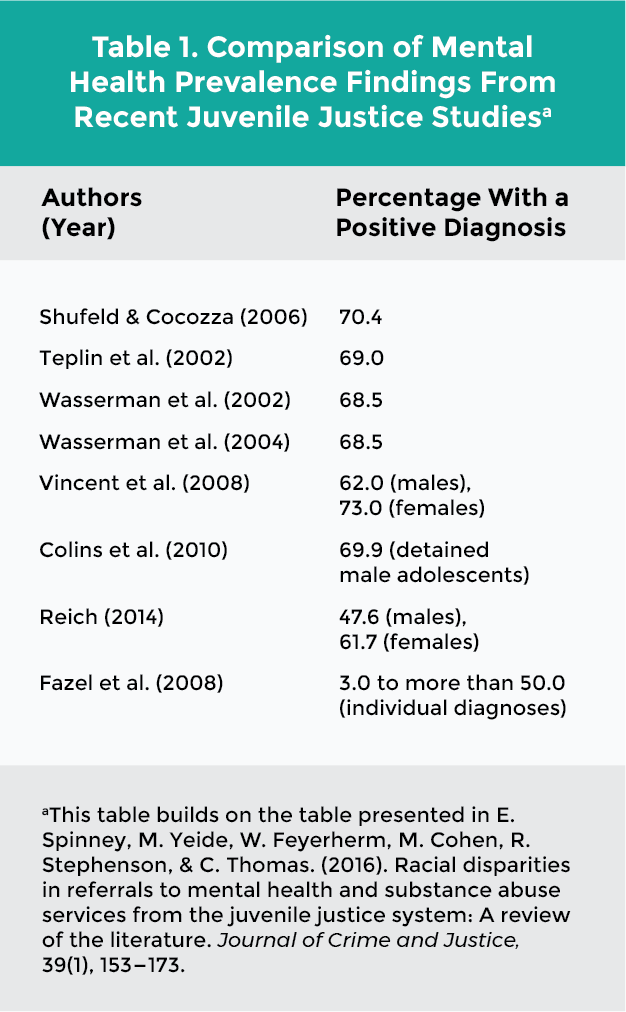

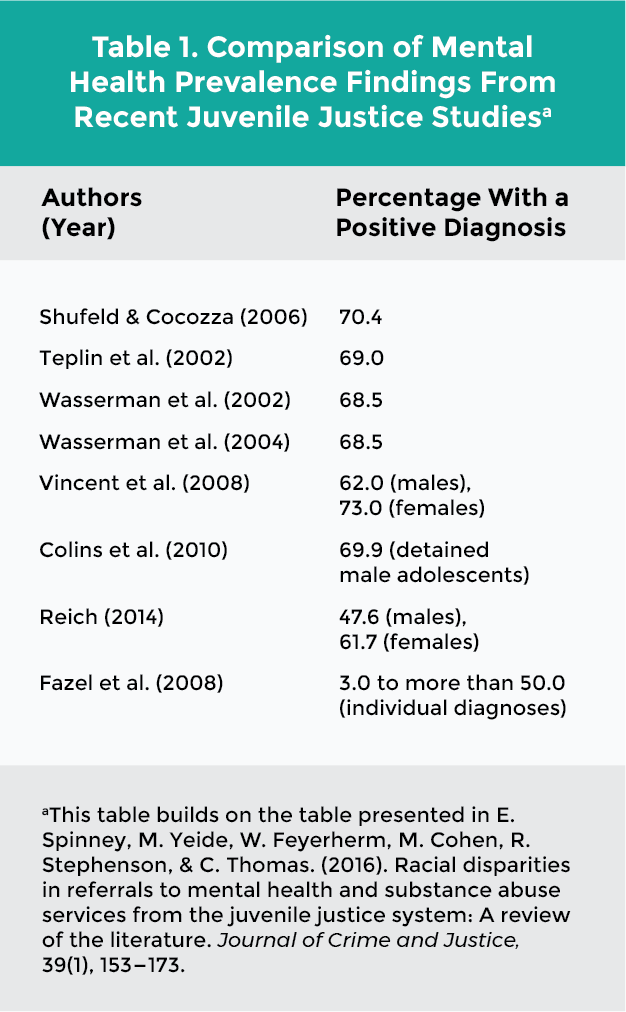

The sad reality is that every year thousands of youths suffering from substance use or mental health problems become entangled with the justice system. This means that justice-involved youths suffer rates of behavioral health issues that far exceed the rates for youths in the general population. Estimates suggest that as many as 70 percent of justice-involved youths have either a mental health or a substance use issue or disorder—or have both. The table below provides findings from recent studies on the prevalence of mental health disorders among juvenile justice populations.1 A Range of Diagnoses

A Range of Diagnoses

The rates are quite stunning, and many youths may present with multiple diagnoses. One study of 1,400 youths found that, of the 70 percent who had one mental health disorder diagnosis, 79 percent met diagnostic criteria for two or more diagnoses.2 Interviews with juvenile detainees in Cook County, Ill., indicated that nearly two thirds of the males and nearly three fourths of females met diagnostic criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders. Among the same group, half of males and almost half of females had a substance use disorder.3

Common diagnoses include

In a study of 64,329 juvenile offenders in Florida, Baglivio and colleagues (2014) found the participants had very high rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—such as emotional or physical abuse, household substance misuse or mental illness—which increase the risk of chronic disease, mental health and substance use disorders, poor academic outcomes, self-harm behaviors, delinquency, and reoffending. More than two thirds of the sample reported three or more ACEs, with females having a higher prevalence rate for all 10 ACEs.7

Limited Referrals to Treatment

Not only are these complex cases challenges to treat, but practitioners in the juvenile justice system also must do so with limited resources. Services are offered in most facilities,8 but only a small proportion of youths who need behavioral health supports and services receive them. Estimates range from a low of 4 percent9 to a high of 23 percent.10 Clearly, this population is underserved overall.

Given the low rate of referral, who actually gets treated? Studies that have looked at predictors of referrals have discovered that referrals are not necessarily based on a mental health diagnosis or need.

Predictors include

Prior mental health service utilization might appear more closely related to mental health needs than the other predictors. But this predictor may be related more to the race/ethnicity of those needing mental health services, for white youths are more likely than minority youths to be served in the community for mental health needs.16 Some studies have even found these racial disparities in prior service use when there were no differences in mental health needs.17

A recent study found that racial disparities play a role in who gets access to mental health and substance use services in the juvenile justice system.18 These disadvantages within the system only exacerbate the disadvantages experienced by youth of color in the community.

Treatment Works

Clearly, treatment is needed. More important, though, treatment works. For example, Hoeve, McReynolds, and Wasserman (2014) found that substance-disordered youths who were referred to mental health/substance use service referrals had lower recidivism risk compared to counterparts without referrals.19 Similarly, Evans Cuellar, McReynolds, and Wasserman (2006) found that juvenile probationers who were assigned to a mental health diversion program were significantly less likely to recidivate in the following years as compared with youth in the waitlist control group.20 Jeong, Lee, and Martin (2013) found that participation in a mental health intervention for youthful offenders was strongly associated with reduced recidivism compared to nonparticipation.21 Colewell, Villarreal, and Espinosa (2012) found that youths who participated in a pre-adjudication diversion initiative using specialized juvenile probation officers were less likely to be adjudicated for the initial offense than a comparison group who received traditional supervision.22

In short, system involvement is almost a sure indicator that behavioral health services are needed. And while youths benefit from these interventions, we as a society at large benefit by reduced long-term costs to the community. As practitioners and advocates for those with behavioral health issues, then, it is important to keep our attention on the juvenile justice system to ensure that it provides adequate care to a highly vulnerable population.

References

The sad reality is that every year thousands of youths suffering from substance use or mental health problems become entangled with the justice system. This means that justice-involved youths suffer rates of behavioral health issues that far exceed the rates for youths in the general population. Estimates suggest that as many as 70 percent of justice-involved youths have either a mental health or a substance use issue or disorder—or have both. The table below provides findings from recent studies on the prevalence of mental health disorders among juvenile justice populations.1

The rates are quite stunning, and many youths may present with multiple diagnoses. One study of 1,400 youths found that, of the 70 percent who had one mental health disorder diagnosis, 79 percent met diagnostic criteria for two or more diagnoses.2 Interviews with juvenile detainees in Cook County, Ill., indicated that nearly two thirds of the males and nearly three fourths of females met diagnostic criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders. Among the same group, half of males and almost half of females had a substance use disorder.3

Common diagnoses include

- Behavior disorders (for example, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder)

- Substance use disorders

- Anxiety disorders (e.g., panic, generalized anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder)

- Mood disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder)

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder4

In a study of 64,329 juvenile offenders in Florida, Baglivio and colleagues (2014) found the participants had very high rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—such as emotional or physical abuse, household substance misuse or mental illness—which increase the risk of chronic disease, mental health and substance use disorders, poor academic outcomes, self-harm behaviors, delinquency, and reoffending. More than two thirds of the sample reported three or more ACEs, with females having a higher prevalence rate for all 10 ACEs.7

Limited Referrals to Treatment

Not only are these complex cases challenges to treat, but practitioners in the juvenile justice system also must do so with limited resources. Services are offered in most facilities,8 but only a small proportion of youths who need behavioral health supports and services receive them. Estimates range from a low of 4 percent9 to a high of 23 percent.10 Clearly, this population is underserved overall.

Given the low rate of referral, who actually gets treated? Studies that have looked at predictors of referrals have discovered that referrals are not necessarily based on a mental health diagnosis or need.

Predictors include

- Age (favoring younger juveniles11)

- Gender (favoring females12)

- Legal factors13

- Geographic region14

- Prior mental health service utilization (favoring those with prior services15)

Prior mental health service utilization might appear more closely related to mental health needs than the other predictors. But this predictor may be related more to the race/ethnicity of those needing mental health services, for white youths are more likely than minority youths to be served in the community for mental health needs.16 Some studies have even found these racial disparities in prior service use when there were no differences in mental health needs.17

A recent study found that racial disparities play a role in who gets access to mental health and substance use services in the juvenile justice system.18 These disadvantages within the system only exacerbate the disadvantages experienced by youth of color in the community.

Treatment Works

Clearly, treatment is needed. More important, though, treatment works. For example, Hoeve, McReynolds, and Wasserman (2014) found that substance-disordered youths who were referred to mental health/substance use service referrals had lower recidivism risk compared to counterparts without referrals.19 Similarly, Evans Cuellar, McReynolds, and Wasserman (2006) found that juvenile probationers who were assigned to a mental health diversion program were significantly less likely to recidivate in the following years as compared with youth in the waitlist control group.20 Jeong, Lee, and Martin (2013) found that participation in a mental health intervention for youthful offenders was strongly associated with reduced recidivism compared to nonparticipation.21 Colewell, Villarreal, and Espinosa (2012) found that youths who participated in a pre-adjudication diversion initiative using specialized juvenile probation officers were less likely to be adjudicated for the initial offense than a comparison group who received traditional supervision.22

In short, system involvement is almost a sure indicator that behavioral health services are needed. And while youths benefit from these interventions, we as a society at large benefit by reduced long-term costs to the community. As practitioners and advocates for those with behavioral health issues, then, it is important to keep our attention on the juvenile justice system to ensure that it provides adequate care to a highly vulnerable population.

References

1For information on prevalence of substance use problems, see A. M. Kopak & S. L. Proctor. (2016). Acute and chronic effects of substance use as predictors of criminal offense types among juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 5(1), 50.

2Shufelt, J. L., & Cocozza, J. J. (2006b). Youth with mental health disorders in the juvenile justice system: Results from a multistate prevalence study. Research and Program Brief. Delmar, N.Y.: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice.

3Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M. K., & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1133–1143. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133

4Chassin, L. 2008. Juvenile justice and substance use. Future of Children, 18(2), 165–183. and Gordon, J. A., & Moore, P. M. (2005). ADHD among incarcerated youth: An investigation on the congruency with ADHD prevalence and correlates among the general population. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(1), 87–97. and Shufelt & Cocozza, 2006b. and Teplin et al.,. 2002. and Yazzie, R. A. (2011). Availability of treatment to youth offenders: Comparison of public versus private programs from a national census. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(6), 804–809. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.11.026

5Riggs Romaine, C. L., Sevin Goldstein, N. E., Hunt, E., & DeMatteo, D. (2011). Traumatic experiences and juvenile amenability: The role of trauma in forensic evaluations and judicial decision-making. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40(5), 363–380. doi: 10.1007/s10566–010–9132–4

6Rosenberg, H. J., Vance, J. E., Rosenberg, S. D., Wolford, G. L., Ashley, S. W., & Howard, M. L.. (2014). Trauma exposure, psychiatric disorders, and resiliency in juvenile justice–involved youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(4), 430–437. doi: 10.1037/a0033199

7Baglivio, M. T., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., & Hardt, N. S. (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1.

8Swank, J. M., & Gagnon, J. C. (2016). Mental health services in juvenile correctional facilities: A national survey of clinical staff. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2862–2872. and Wiblishauser, M., Jordan, T. R., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., & Jenkins, M. (2015). Substance use services for adolescents in juvenile correctional facilities: A national study. Journal of juvenile justice, 4(2), 13.

9Breda, C. S. (2003). Offender ethnicity and mental health service referrals from juvenile courts. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(6), 644–667. doi:10.1177/0093854803256451

10Shelton, D. 2005. Patterns of treatment services and costs for young offenders with mental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18(3), 103–112.

11Herz, D. C. 2001. Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v

12Gunter–Justice, T. D., & Ott, D. A. 1997. Who does the family court refer for psychiatric services? Journal of Forensic Sciences, 42(6), 1104–1106. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.377. and Herz, D. C. 2001. Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v. and Rogers, K. M., Zima, B., Powell, E., & Pumariega, A. J. (2001). Who is referred to mental health services in the juvenile justice system? Journal of Child & Family Studies, 10(4), 485–494. doi: 1062–1024/01/1200–0485/0 and Rogers, K. M., Pumariega, A. J., & Cuffe, S. P. (2001). Identification and referral for mental health services in juvenile detention. In 14th Annual Research Conference, A System of Care for Children’s Mental Health, edited by C. Newman, C. Liberton, K. Kutash and R. Friedman. Tampa, Fla.: Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health, University of South Florida.

13Breda, 2003. and Rogers, K. M., Pumariega, A. J., Atkins, D. L., & Cuffe, S. P. (2006). Conditions associated with identification of mentally ill youths in juvenile detention. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(1), 25–40. doi:10.1007/s10597–005–9001–z and Yan, J., & Dannerbeck, A. (2011). Exploring the relationship between gender, mental health needs, and treatment orders in a metropolitan juvenile court. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 20(1), 9–22. doi: 10.1007/s10826–010–9373–8

14Herz, D. C. (2001). Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v. and Shufelt, J. L., & Cocozza, J. J. (2006a). Past and current service utilization among youth in the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) multistate study. In C. Newman, C. Liberton, K. Kutash, & R. Friedman (Eds.). Nineteenth Annual Research Conference Proceedings: A System of Care for Children’s Mental Health, Expanding the Research Base, Tampa, Fla.: Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health, University of South Florida.

15Barnes, J. C., Miller, H. V., & Mitchell Miller, J. (2009). Identifying leading characteristics associated with juvenile drug court admission and success: A research note. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(4), 350–360. doi: 10.1177/1541204009334630. and Dalton, R. F., Evans, L. J., Cruise, K. R., Feinstein, R. A., & Kendrick, R. F. (2009). Race differences in mental health service access in a secure male juvenile justice facility. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 48(3), 194–209. doi: 10.1080/10509670902766570. and Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Washburn, J. J., & Pikus, A. K. (2005). Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: Who receives services? American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1773–1780. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.067819

16(Barksdale, Azur, & Leaf 2010; Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells 2002) Barksdale, C. L., Azur, M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Differences in mental health service sector utilization among African American and Caucasian youth entering systems of care programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 363–373. doi:10.1007/s11414–009–9166–2. and Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. 2002. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159 (9), 1548–1555. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548

17Kates, E., Gerber, E. B., & Casey, S. 2014. Prior service utilization in detained youth with mental health needs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10488–012–0438–4

18Spinney et al., 2016.

19Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L., & Wasserman, G. (2014). Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, 41(3), 379–389. doi:10.1007/s10488–013–0472–x

20Evans Cuellar, A., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2006). A cure for crime: Can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25(1), 197–214.

21Jeong, S., Lee, B. H., & Martin, J. H. 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of a special needs diversionary program in reducing reoffending among mentally ill youthful offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(9), 1058–1080. doi:10.1177/0306624x13492403

22Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary outcomes of a pre-adjudication diversion initiative for juvenile justice–involved youth with mental health needs in Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460.

Spinney et al., 2016.

Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L., & Wasserman, G. (2014). Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, 41(3), 379–389. doi:10.1007/s10488–013–0472–x

Evans Cuellar, A., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2006). A cure for crime: Can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25(1), 197–214.

Jeong, S., Lee, B. H., & Martin, J. H. 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of a special needs diversionary program in reducing reoffending among mentally ill youthful offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(9), 1058–1080. doi:10.1177/0306624x13492403

Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary outcomes of a pre-adjudication diversion initiative for juvenile justice–involved youth with mental health needs in Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460.

2Shufelt, J. L., & Cocozza, J. J. (2006b). Youth with mental health disorders in the juvenile justice system: Results from a multistate prevalence study. Research and Program Brief. Delmar, N.Y.: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice.

3Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M. K., & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1133–1143. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133

4Chassin, L. 2008. Juvenile justice and substance use. Future of Children, 18(2), 165–183. and Gordon, J. A., & Moore, P. M. (2005). ADHD among incarcerated youth: An investigation on the congruency with ADHD prevalence and correlates among the general population. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(1), 87–97. and Shufelt & Cocozza, 2006b. and Teplin et al.,. 2002. and Yazzie, R. A. (2011). Availability of treatment to youth offenders: Comparison of public versus private programs from a national census. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(6), 804–809. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.11.026

5Riggs Romaine, C. L., Sevin Goldstein, N. E., Hunt, E., & DeMatteo, D. (2011). Traumatic experiences and juvenile amenability: The role of trauma in forensic evaluations and judicial decision-making. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40(5), 363–380. doi: 10.1007/s10566–010–9132–4

6Rosenberg, H. J., Vance, J. E., Rosenberg, S. D., Wolford, G. L., Ashley, S. W., & Howard, M. L.. (2014). Trauma exposure, psychiatric disorders, and resiliency in juvenile justice–involved youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(4), 430–437. doi: 10.1037/a0033199

7Baglivio, M. T., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., & Hardt, N. S. (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1.

8Swank, J. M., & Gagnon, J. C. (2016). Mental health services in juvenile correctional facilities: A national survey of clinical staff. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2862–2872. and Wiblishauser, M., Jordan, T. R., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., & Jenkins, M. (2015). Substance use services for adolescents in juvenile correctional facilities: A national study. Journal of juvenile justice, 4(2), 13.

9Breda, C. S. (2003). Offender ethnicity and mental health service referrals from juvenile courts. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(6), 644–667. doi:10.1177/0093854803256451

10Shelton, D. 2005. Patterns of treatment services and costs for young offenders with mental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18(3), 103–112.

11Herz, D. C. 2001. Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v

12Gunter–Justice, T. D., & Ott, D. A. 1997. Who does the family court refer for psychiatric services? Journal of Forensic Sciences, 42(6), 1104–1106. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.377. and Herz, D. C. 2001. Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v. and Rogers, K. M., Zima, B., Powell, E., & Pumariega, A. J. (2001). Who is referred to mental health services in the juvenile justice system? Journal of Child & Family Studies, 10(4), 485–494. doi: 1062–1024/01/1200–0485/0 and Rogers, K. M., Pumariega, A. J., & Cuffe, S. P. (2001). Identification and referral for mental health services in juvenile detention. In 14th Annual Research Conference, A System of Care for Children’s Mental Health, edited by C. Newman, C. Liberton, K. Kutash and R. Friedman. Tampa, Fla.: Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health, University of South Florida.

13Breda, 2003. and Rogers, K. M., Pumariega, A. J., Atkins, D. L., & Cuffe, S. P. (2006). Conditions associated with identification of mentally ill youths in juvenile detention. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(1), 25–40. doi:10.1007/s10597–005–9001–z and Yan, J., & Dannerbeck, A. (2011). Exploring the relationship between gender, mental health needs, and treatment orders in a metropolitan juvenile court. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 20(1), 9–22. doi: 10.1007/s10826–010–9373–8

14Herz, D. C. (2001). Understanding the use of mental health placements by the juvenile justice system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900303v. and Shufelt, J. L., & Cocozza, J. J. (2006a). Past and current service utilization among youth in the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) multistate study. In C. Newman, C. Liberton, K. Kutash, & R. Friedman (Eds.). Nineteenth Annual Research Conference Proceedings: A System of Care for Children’s Mental Health, Expanding the Research Base, Tampa, Fla.: Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health, University of South Florida.

15Barnes, J. C., Miller, H. V., & Mitchell Miller, J. (2009). Identifying leading characteristics associated with juvenile drug court admission and success: A research note. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(4), 350–360. doi: 10.1177/1541204009334630. and Dalton, R. F., Evans, L. J., Cruise, K. R., Feinstein, R. A., & Kendrick, R. F. (2009). Race differences in mental health service access in a secure male juvenile justice facility. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 48(3), 194–209. doi: 10.1080/10509670902766570. and Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Washburn, J. J., & Pikus, A. K. (2005). Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: Who receives services? American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1773–1780. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.067819

16(Barksdale, Azur, & Leaf 2010; Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells 2002) Barksdale, C. L., Azur, M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Differences in mental health service sector utilization among African American and Caucasian youth entering systems of care programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37, 363–373. doi:10.1007/s11414–009–9166–2. and Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. 2002. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159 (9), 1548–1555. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548

17Kates, E., Gerber, E. B., & Casey, S. 2014. Prior service utilization in detained youth with mental health needs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10488–012–0438–4

18Spinney et al., 2016.

19Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L., & Wasserman, G. (2014). Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, 41(3), 379–389. doi:10.1007/s10488–013–0472–x

20Evans Cuellar, A., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2006). A cure for crime: Can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25(1), 197–214.

21Jeong, S., Lee, B. H., & Martin, J. H. 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of a special needs diversionary program in reducing reoffending among mentally ill youthful offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(9), 1058–1080. doi:10.1177/0306624x13492403

22Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary outcomes of a pre-adjudication diversion initiative for juvenile justice–involved youth with mental health needs in Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460.

Spinney et al., 2016.

Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L., & Wasserman, G. (2014). Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, 41(3), 379–389. doi:10.1007/s10488–013–0472–x

Evans Cuellar, A., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2006). A cure for crime: Can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25(1), 197–214.

Jeong, S., Lee, B. H., & Martin, J. H. 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of a special needs diversionary program in reducing reoffending among mentally ill youthful offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(9), 1058–1080. doi:10.1177/0306624x13492403

Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary outcomes of a pre-adjudication diversion initiative for juvenile justice–involved youth with mental health needs in Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460.