|

THE MAINE IDEA: PORTLAND DEFENDING CHILDHOOD SCREENS FOR CHILDREN EXPOSED TO VIOLENCE

|

by Marla Fogelman

“We can’t help children who have experienced trauma… if we don’t know who they are.”

—from the Portland Defending Childhood Screening Initiative

Childhood exposure to violence (CEV), a public health crisis that has left its mark on roughly two out of every three children in the United States,1 damages not only the psyches of those children but also their growth and development. As multiple studies have indicated, when children are subjected to severe or repeated abuse or violence—especially during such critical, developmental periods as infancy and early childhood—they may experience real and toxic changes in their brain architecture.2 These changes can then disrupt their ability to progress through normal milestones and grow into healthy, well-functioning adults.

But despite the destabilizing and detrimental effects of CEV—as well as its prevalence—a groundbreaking, evidence-informed, screening initiative by Portland (Maine) Defending Childhood (PDC) is providing a first-line strategy for helping pinpoint and thus mitigate CEV’s impact. In November 2015, PDC in partnership with Maine Medical Center rolled out a pediatric screening program to identify those children and youths who may have experienced trauma as a result of being exposed to violence, and to give them and their families the help they need.

|

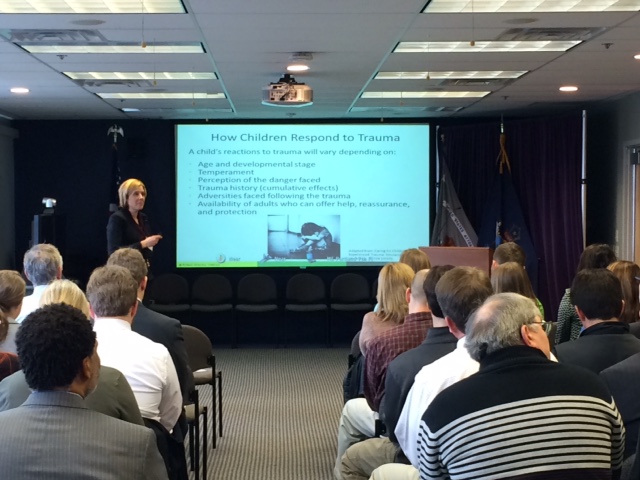

| Portland (Maine) Defending Childhood’s Rebecca Brown facilitates a training on childhood exposure to violence, in April 2005, to federal prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Maine, in Portland.

|

Characterizing the PDC–Maine Medical Center partnership as a “true collaboration,” PDC Prevention Coordinator Barrett Wilkinson said that the impetus for their collaboration began 2 years earlier, when the hospital realized that PDC’s proposed initiative “dovetailed with what they were seeing in their emergency rooms and pediatric outpatient clinics.”

Specifically, as Maine Medical Center’s Stephen DiGiovanni noted, “We were seeing two different trauma-exposed populations: one in which there has been multigenerational abuse and violence, and another [that] is an international refugee population.”

Maine’s Children and CEV

By any measure, Maine’s children and youths have had more than their share of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which may include abuse, neglect, or having a parent with a mental illness or substance use disorder.3

The 2015 data book Maine Kids Count,4 compiled by the Maine Children’s Alliance, showed that 25.1 percent of the state’s children, ages 0–17, had experienced two or more ACEs, compared with 22.6 percent of children in this age range nationwide.

And for Portland’s youth in particular, an ACE would likely involve exposure to domestic violence, which is, according to PDC Project Coordinator Aurora Smaldone, the most prevalent form of violence in the city.

But as research also indicates, support from caring adults in the family and community can provide a protective effect.5 Thus PDC in 2013 began making plans for the implementation of a universal screening system that would also incorporate best practices, technical assistance, and lessons learned.

To put this first-of-its-kind program into place, Smaldone said that PDC began by assembling a steering committee to look at whether the panel could screen in a way “that would enable providers to identify kids who had been exposed to violence.” She said that PDC’s aim was to convey to pediatric providers just how strongly CEV influences child development, so that they would then be able to refer their patients to the appropriate services or programs.

Together with the help of Dr. DiGiovanni, who serves as director of Maine Medical Partners Outpatient Clinics, PDC then presented information on CEV to medical students, residents, and physicians at pediatric grand rounds.

Pilot Program

In January 2015, PDC conducted a 6-month, pilot screening program at a pediatric outpatient clinic at Maine Medical Center, as the beginning of an effort to embed its screening protocol into the electronic medical record (EMR) system of MaineHealth, a delivery network that encompasses the majority of healthcare providers and organizations throughout the state.

To identify CEV and trauma, PDC had providers ask their patients the following two screening questions, which were devised from recommendations from pediatric and psychiatric experts:6

- Do you feel safe in your home, neighborhood, school, relationships?

- Has anything bad, sad, scary happened to you in the past year?

|

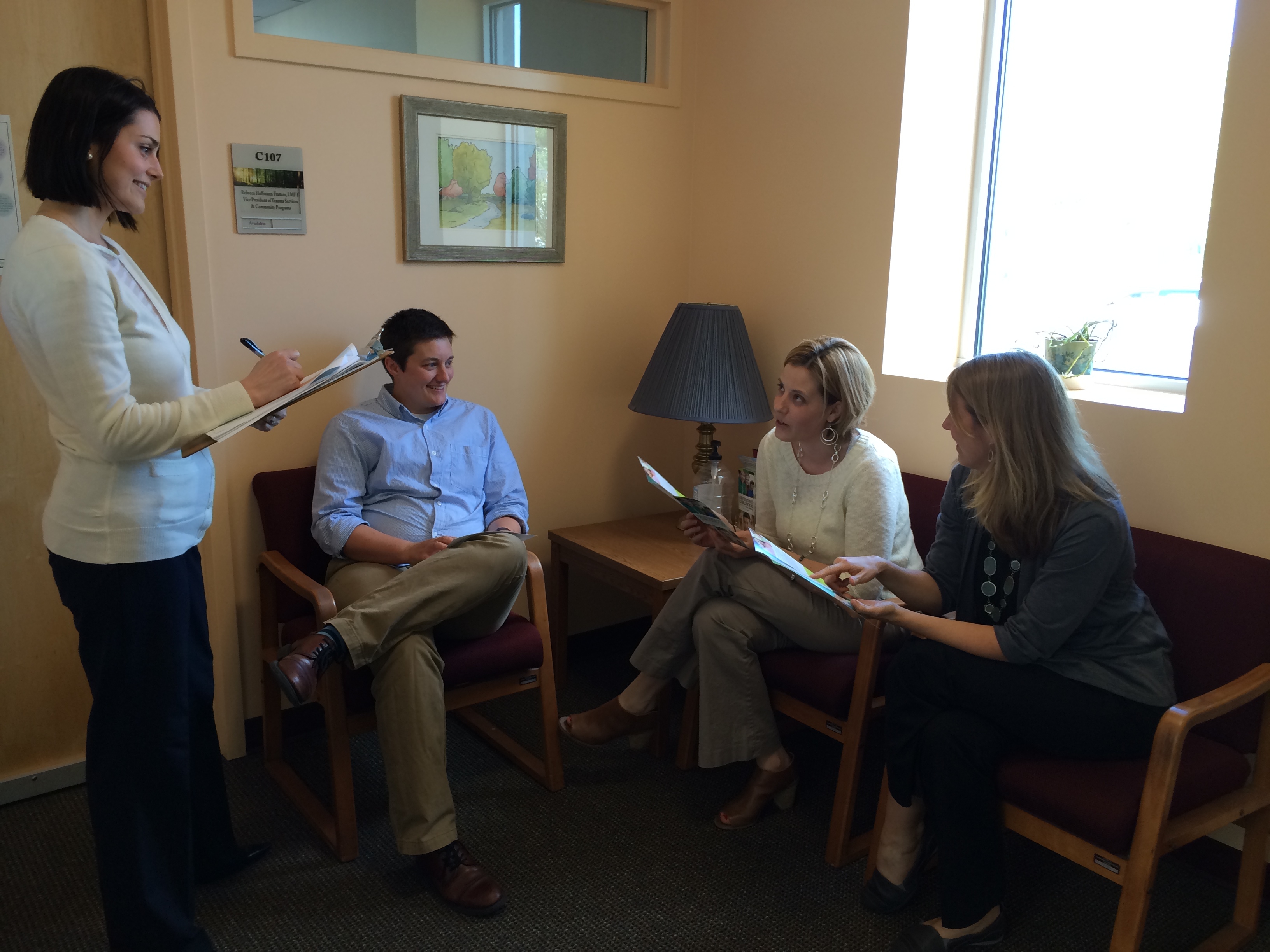

| Portland Defending Childhood staff (from left) Aurora Smaldone, Barrett Wilkerson, Rebecca Brown, and Dory Hacker, at PDC’s clinical headquarters, Portland, Maine.

|

For further assessment, they employed the abbreviated Posttraumatic Stress Disorder–Reaction Index for Children and Adolescents, a tool that evaluates the presence and degree of traumatic stress reactions.

The results of the trial program demonstrated why screening can be an important first step in protecting children and their development. Smaldone said that, through the pilot, pediatric providers were able to find “positive screens” for children who had not before been identified.

Program Launch and Training

By the end of 2015, the screening protocol had been successfully incorporated into the EMR system. After designing a resource toolkit for providers, PDC also began conducting training for pediatricians and family medicine practitioners at 15 to 25 sites throughout Portland. The training included a slide presentation on the short- and long-term effects of CEV and trauma, the role of pediatric providers in addressing the issue, and the core components of the screening process—from identifying a child at risk to getting the child immediately into safety, providing guidance to the child’s caregiver, closely monitoring the child and family’s situation, and/or referring the child for one of three types of evidence-based treatment, depending on the child’s age and type of violence exposure (see figure below).

According to Smaldone, the providers’ reactions to the training “have been overwhelmingly positive, underscoring the importance of looking at CEV as a universal healthcare issue.” She said that PDC has also found it particularly gratifying to have doctors acting as “internal systems champions” of universal screening.

Success and the Future

Although the program is still in its beginning stages, PDC has received encouraging case reports from individual providers. Smaldone cited one of a middle schooler who described being the victim of a home break-in, at night, while the family was asleep; and another of a teen patient who had been threatened with a gun at a convenience store. In both cases, because of the screening program, these children were able to get follow-up support and further monitoring from mental health professionals.

Currently, Smaldone said that PDC is developing an e-learning module that can be used to train other providers throughout the state. And she believes that this model for identifying and addressing CEV could be used even more widely to help ease this national crisis.

For DiGiovanni, the partnership with PDC has not only been “fantastic” but also critical in helping to raise awareness of the issue of CEV among pediatric providers.

“Pediatrics is moving in this direction,” said DiGiovanni. “But with this initiative, that’s the kind of change you can help push forward.”

References

| 1 |

Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. 2012. Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Washington, D.C.: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. |

| 2 |

Victor G. Carrion, Carl F. Weems, and Allan L. Reiss. 2007. “Stress Predicts Brain Changes in Children: A Pilot Longitudinal Study on Youth Stress, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and the Hippocampus.” Pediatrics 119(3). |

| 3 |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2016. “Adverse Childhood Experiences.” |

| 4 |

Maine Children’s Alliance. 2015. Maine Kids Count Data Book. Augusta, Maine: Maine Children’s Alliance. |

| 5 |

Jack P. Shonkoff, Andrew S. Garner, and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2012. “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress.” Pediatrics 129:e232–e46. |

| 6 |

Judith Cohen, Kelly J. Kelleher, and Anthony Mannarino. 2008. “Identifying and Referring Traumatized Children: The Role of Pediatric Providers.” Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 162(5):447–52. |

|

|

|